Nineteenth Century Assamese Society & Casteism Through The Lens of Homen Borgohain’s Motsyogondha

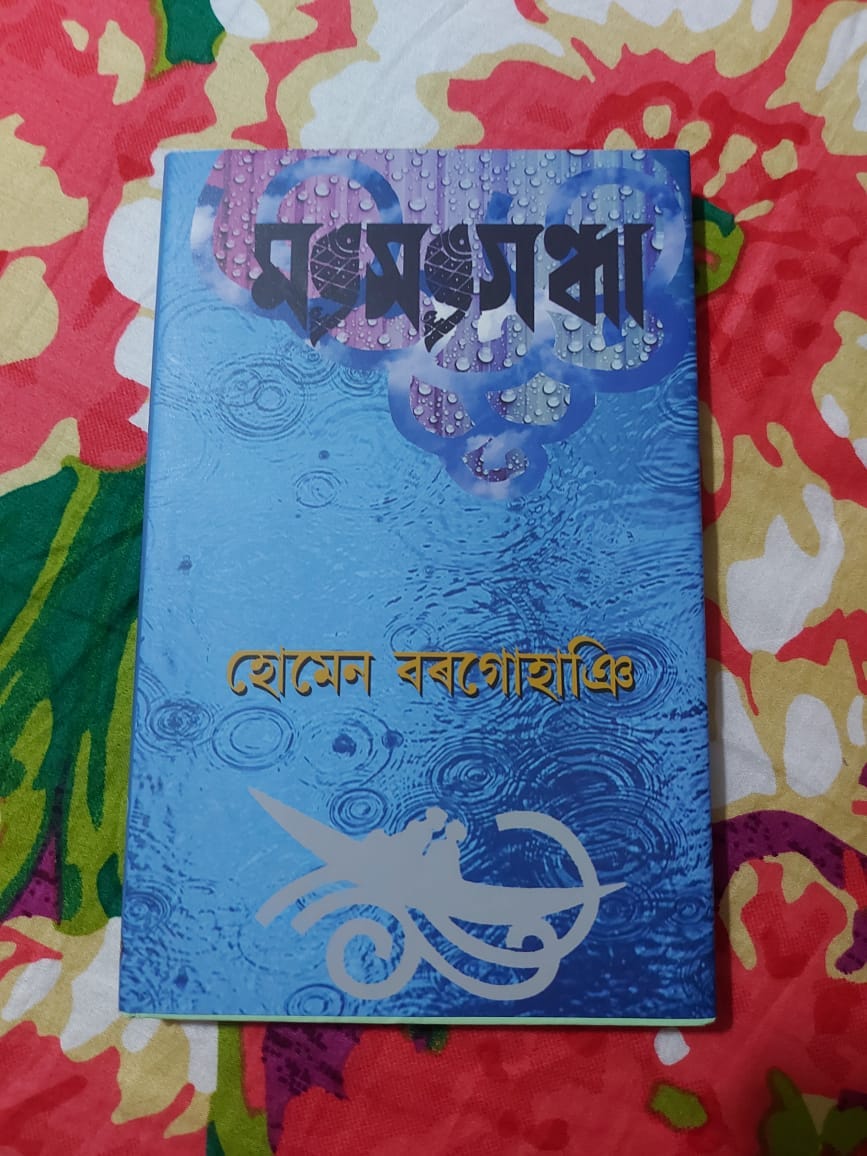

A masterpiece work of Assamese literature by the late novelist Homen Borgohain, Motsyogondha, literally translates to ‘The Fisherman’s Daughter’. Published on July, 1987, the theme that its story revolves around makes Motsyogondha a true piece of progressive literature in the history of Assamese literary works.

Set in the Goroimari village of Assam, Motsyogondha centres around its fierce female protagonist, Menoka. The novel deals with the ugliness of untouchability and caste system in the society. Through its protagonist, the novel addresses the economic instability, struggles and discrimination faced by the people of the Dom or the Koiborto caste, a community of fishermen in Assam. It also points out the long prevailing issue of opium consumption in Assam and its vicious grip within the society.

The story begins with the protagonist’s struggle to sleep because of her failure to manage food for the particular night and even more importantly, opium, without the consumption of which sleeping was an out of question for her. Mostly, except the last two chapters in the climax, set within the course of that one night, the story, however, moves back and forth in a sequence of flashback wherein Menoka recalls her life from childhood to adulthood and her experiences of hailing from a forbidden caste of the society. As the story progresses it starts narrating the story of another major character, Komola, who falls in love with an Ahom boy of high-status in the society and gets impregnated by him. The story also revolves around the flashbacks of Komola’s life as she narrates her story with Moniram to the protagonist, who’s apparently her sister-in-law. By the near climax of the novel, while Moniram initially refuses to accept his responsibility of being the father to Komola’s unborn child and therefore marry her, Menoka’s fierce threatening, however, finally scares and forces him to do so but as a result gets outcasted from his family and the community.

The evils of untouchability in the society can be seen in the story in various scenes of the novel. One such instance is when Menoka recalls one of her childhood incidents. Once, as a child, unaware of the ugly norms of the society, she accidentally goes near an upper caste household’s courtyard where paddies were kept down to dry in the sun. The falling of her shadow on the paddy made it impure and polluted for the upper caste to consume. Menoka then suddenly gets a hard tight slap she was unprepared for from the lady of the house for the sin she committed and thereafter, witnesses the lady commanding the servant to use it for feeding the cows since it’s now of no use for the household. The hypocrisy of the so-called upper caste of the society can be seen here when the lady on one hand considers even the shadow of Menoka as being impure but at the same time touching her to slap her for the crime she committed, the lady felt was alright.

On another instance, Digombor, who apparently is Menoka’s father-in-law, in the past dreams of giving education to both his sons. Digombor manages to get his sons secure admission to the nearby village government school with the hope that his sons will become educated individuals in the future. However, facing daily humiliations from their fellow classmates and discriminations from the teachers because of their status in the society both the kids after a certain point unable to bear it anymore drops out from school. The darker sides of casteism can be seen herein again.

The novel also depicts how weaker section of the society at times need to come in terms with adjustments for the convenience of those on the upper level. This can be seen during the festive season of bihu. Traditionally, during the season of bihu, youths (both, boys & girls) in villages of Assam those populated with the Koiborto, Kochari, Ahom and Mishing community performs bihu the whole night in the village common ground. The Doms or the Koiborto people of the Goroimari village, however, fears to do the same because of the fact that almost five to six villages surrounding Goroimari are those of the Brahmin, Kolita, Koch and Chutia community who disapproves this custom of youths dancing in the open common ground. The people of Goroimari depends a lot on the residents of these surrounding villages for economic assistance from time to time and hence, needs to remain in their good books. It is, therefore, that the Koibortos of Goroimari only for the sake of keeping their age-old tradition alive performs bihu in the common ground till the sunsets and wraps up once the sun goes down.

Finally, the novel narrates the ancient issue of male dominance in a patriarchal society. The ever-prevalent age-old mentality of viewing women as a mere toy of sexual pleasure by men is depicted through Moniram’s character who for his selfish desires lures Komola into believing that he will marry her. His mentality about women gets more visible when initially he tries to control his desires for Komola because of the social difference between them by telling to himself that, “Moniram have you forgotten about Thurimola? What does Thurimola lacks in comparison to this Komola? Just three months more and you are going to get married to her. For your entire life you are going to get a beautiful girl like her as the women of your bed.” That’s what Moniram thinks of women; women in Moniram’s view are just things to enjoy and sleep with in the bed, be it Komola or Thurimola. The hypocrisy of the caste system can be seen here again when Moniram for his sexual desire don’t hesitate to establish physical contact with Komola but, later hesitates to marry her because of her social status. Moniram’s hypocrisy can also be seen in his polite and decent behaviour towards Menoka after he comes to know about Komola’s pregnancy, to the extent that he even offers water to Menoka in the same bowl kept for his own use. This change in Moniram’s behaviour was in hope of pity and mercy from Menoka in the matter which he however, fails to gain.

The novel on one hand while portrays the sufferings of the lower caste and their struggles of daily life, it on the other hand also shows that despite their economic and social status, there are people who dares to dream and hope for a better future and works hard to fulfil those dreams. Characters like Duryodhan, Digombor and Joyhori are such progressive torchbearers of the society who works hard to achieve a better economic condition by going beyond their traditional means of livelihood. Also, through fierce & strong protagonist like Menoka it portrays that despite being a low caste she had strong will power to fight against the society’s evil norms and atrocities and takes pride in her identity as a Dom.

Motsyogondha, was indeed a brave work of literature by Borgohain not only because of its strong theme but also because it takes lots of courage and progressive mentality for an author to portray a primarily negative character in the novel as an individual from the community that the author himself belongs to. Borgohain himself being an Ahom of high social status didn’t hesitate to portray the character of Moniram as an Ahom. While speaking of the ills that the socially privileged section of the society has committed over the weaker, Borgohain indiscriminately voiced out that his own community is no less sinful of these doings and is at equal fault as many others for the crimes of casteism committed.

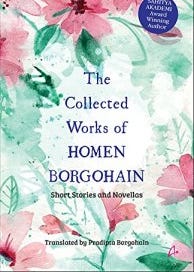

Motsyogondha has been translated into English as ‘The Fisherman’s Daughter’ by the late author’s son Pradipta Borgohain and published by Amaryllis publication as ‘The Collected Works of Homen Borgohain: Short Stories and Novellas’. The collection also includes his other works such as, Xaudor Puteke Nau Meli Jai (The Merchant’s Son Sets Sail) and 12 other short stories.